FENCEROWS...State of the Wolf

By John Luthens

It is now into the second week of the gray wolf hunting season, with DNR reports showing 16 registered wolves in the first week, taken from the six divided zones cut through the landscape of our state.

The zones are simply arbitrary lines on a map. They are a mere formality, designed to add a human semblance to the wilderness haunts where the wolves really are. The number 16 was high enough to surprise me this early in the season, because while wolves can be social enough amongst their own pack, they can be hard as hell to hunt. But then again, Wisconsin does have some of the finest hunters in the nation.

So far, the majority of wolves have been taken in the northern tier of Wisconsin, and it’s a parcel of territory that I have crossed and re-crossed for many years, spending a mind-boggling amount of hours in tangles, rivers and forests, and on back-country logging lanes. I have seen the tracks, I know they are there, and I think everyone in my family has seen at least one, but I have yet to encounter a wild wolf up close and personal.

What I have seen, is a long, often confusing, trail of wolf-recovery action.

A message from the past.

I have witnessed the lunch counters and watering holes where you talk to the local patrons about fishing, hunting, or the outdoors in general and receive fond smiles and fonder stories; but mention timber wolves, and you risk starting a bar-room brawl.

I’ve talked to farmers with wolf-depredation losses. I’ve written stories. I found one in my archives just this week that was written in 2004, when the timber wolf was still on the federally threatened list, and when it was still under the black-op northern hunting status of what some called the three S’s: Shoot, shovel, and shut-up.

I have been to Northland College in Ashland for Timber Wolf Awareness week, held annually over the third week in October, and sponsored by The Timber Wolf Alliance, which was formed in 1987 to work with communities on wolf-related environmental issues.

I’ve read surveys, like the one I used in my 2004 story, circulated by Kevin Schanning, who is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Northland College. It was designed around a principle that it was not in spite of disagreements, but through them, that solutions to Wisconsin timber wolf management could be found.

The research data from my story, from the ancient history of eight long years ago, reported that 13.3% of those who responded to Schanning’s survey strongly supported a public hunting season on wolves. That didn’t seem like a high percentage at the time.

We have come a long way since then. We as sportsmen, conservationists, and as individuals who truly care for the welfare of the state’s economy have a true shot at getting something right here, and in my opinion, it’s something we have failed at so far. I don’t think we’ve failed on purpose, and I believe there are many valid reasons behind it.

I don’t own a farm. My livelihood doesn’t depending on stock grazing in the fields. If I did though, and I was losing money because of wolf depredation on my herd, I can’t say I’d be too happy. I would want the state to reimburse me for wolf losses, and I would understand why my ancestors in the Wisconsin farming industry considered the wolf to be a stealing varmint that should be wiped from the landscape.

But I’m also not an animal rights activist. I believe that the predator-prey scenario is what makes the natural world tick. The wolf is an apex predator. It has a valid place in the natural scope of the landscape. I believe that that the wolf does a finer job of managing a deer herd than any state-developed management plan.

That being said, the wolf has re-entered Wisconsin through a time machine, coming back to a modern ecological system that is far removed from the endless forested lands that the state once harbored. That can’t happen without problems.

So we must manage it the best we can, and I don’t believe we need to expatriate the wolf entirely to do that. We just have to do our part by hunting them, and the historic season that got under way last week is a vital link. Humans are the only real predator the timber wolf has.

Do timber wolves kill deer? Yes they do. But with proper management, we can have the best of all worlds. Balancing a healthy deer herd, and by that I mean healthy deer, besides pure numbers. The wolves will necessarily weed out what they find to be the easiest prey. In hard winters, I tend to think the wolves will take the deer that run the highest risk of not making it through.

Hard winters will kill the weaker wolves too, so it only makes sense to harvest them in a sporting way.

We can continue to pay into the wolf-depredation fund, but wolves are highly intelligent. I believe it won’t take them long to figure out what it means to scent a human habitation after a couple of seasons. Money raised in the sale of wolf harvest tags can go to depredation costs along with the wolf-recovery fund, so we can have more wolves to hunt, and it becomes a happy cycle.

These are not original ideas. I’m fairly certain they have been hashed and rehashed at every level of state wildlife management. I know for a fact they’ve been gone over at every diner, tavern, and sports shop that I’ve encountered in my travels.

Everyone involved is entitled to their opinion, because this is the greatest and most democratic land there is, and just like the natural cycle of nature, it is supposed to work that way. But just having those opinions doesn’t guarantee that they are correct. I tend to think that if we took all ideas and opinions on timber wolf management, without getting too clouded with anger, and threw them in a hat, we would come out with a good long-term solution that would benefit everyone.

So now that I’ve written my humble opinion, I’ve still yet to see a wild wolf. I hope to be lucky enough to draw a permit someday and try. For now, all my experience, and most of my thoughts on the timber wolf, boils down to an abandoned hunting shack I once came across in my ramblings through the northern forest land of the Lake Superior country.

The shack was near impossible to see, and it was nothing but pure accident that brought me onto its weathered porch steps, set off a dirt road under poplars and pines, with no drive leading to it and no sign of habitation for many years. It was peeled and warped, and I expected to bust through the floor boards when I poked inside.

Porcupines had chewed through a pair of old mattresses on a bunk bed, and an old wood stove rusted in a corner. There was a card table, empty rotted cupboards, and not much else. I knew it to be an old hunting shack, because it still held that magic feeling in the dark and musty air that all hunters can recognize.

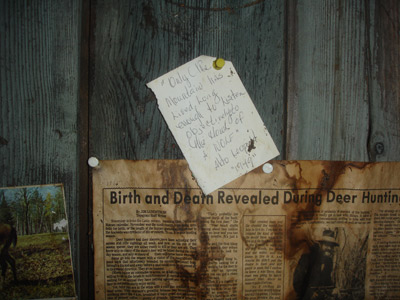

There was a picture of a deer hunter in an old bearskin coat, holding a rifle. The newsprint it was printed on was faded and yellowed. Then was a single quote tacked on a note card next to the clipping: “Only the mountain has lived long enough to listen objectively to the howl of a wolf.”

It was a quote from Aldo Leopold, dated 1949 on the note card. I left the shack, feeling I was trespassing upon opinions much deeper than my own. I’ve never been back. But the scribbled thoughts from the abandoned hunting camp wall have followed me out like a trailing wolf.