Winneboujou

By John Luthens

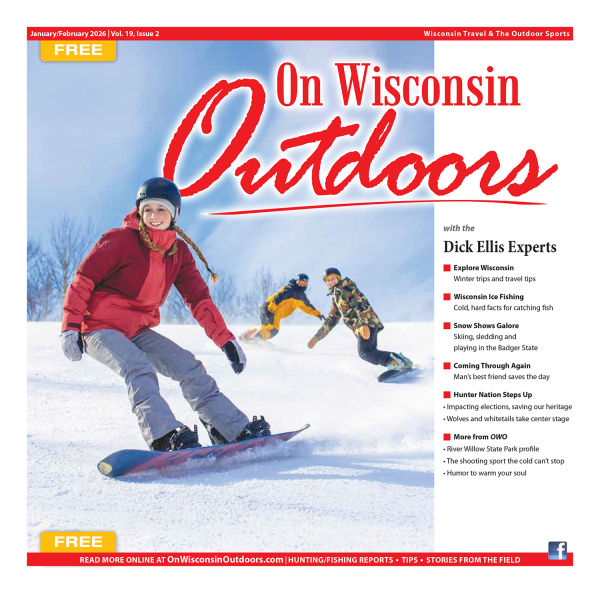

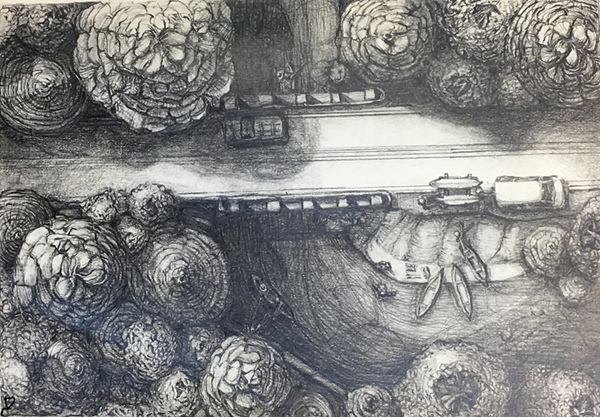

The Winneboujou Bridge, spanning the Bois Brule River in northern Douglas County. (Pencil Sketch by Daniel Luthens)

Tucked beneath red-pine shadows in a furthest corner of northwest Wisconsin is a bridge named Winneboujou; stone pilings stretching their rounded fingers into the spring-clear passage of the Bois Brule River at the bottom of a plunging drop along Douglas County’s Highway B.

Now, a casual observer paging through the blueprints of architects and road designers might say that Winneboujou’s engineered surface is no different than any other bridge. It’s streamlined surface appears to function find and dandy as a safe portage across the steep banks of the Brule and yields a smooth, windowed passage above the swirling rush below.

Viewing Winneboujou in its northern flesh and blood is a different story. A distinct air of unordinary hovers beneath the rolling blacktop and iron rails – something in its nature that nudges it a bit out of focus with the common world. It’s hard to put a finger on, exactly, but perhaps the closest one can come to explaining is to say that it’s outline against the backdrop of the Brule River Valley is a little hazy around the edges, almost as if the bridge itself seems unsure of the asphalt across its back and is wavering back and forth in time.

Once a railway trestle and whistling, train-stop depot for timber speculators and far-going sportsman; once a simple wagon bridge creaking under the weight of moving settlers, and before that, possibly nothing more than a white pine giant crashed over the rolling river Brule. Native American legends tell of the great god Winneboujou hammering on his anvil and creating northern life. Perhaps it was he who first spanned the crossing that bears his sacred name.

Maybe it’s the smell of pine pitch rising like an invisible mist, or the tentative rise of a trout in the overhung alders below, or it could be the silent, almost ghostly, appearance of a wooden canoe in the riffles above the bridge and the whistling, siren song of age-old fly line, disappearing as quickly as it came with the echo of wooden paddles biting water around the bend on the other side. Winneboujou’s anvil rings through the valley in many different echoes.

Hurried travelers crossing the bridge have been known to brake suddenly and leave their modern rides sputtering in the northern breeze, plucked like a mayfly from itineraries and deadlines to peer over the railing at speckled visions of silver tails and gold-spotted shadows in the water. Sometimes, when the sun slants through the pine tops just right, certain angling-mined wayfarers have been pulled with a solid splash into the pooled light beneath Winneboujou itself to go missing for hours at a crack.

It may sound silly to think of a simple bridge as a living and breathing entity, but I’ve come to believe that the spirits living beneath its awning can’t be rationalized away in any other modern context. I’ve seen Winneboujou’s magic first-hand, coming of age a fly cast away, spending endless summers at my grandfather’s cabin above the crossing and many an hour lost in the bridge’s spell.

I hooked my first Brule River trout in the swirling pool below, a spotted brown monster that rushed from beneath a fallen pine tangle to smash my tackle and spit it back in my face in one fell leap. I’ve lost plenty trout since, but dreams of Winneboujou still wake me up nights in a cold and shaking sweat.

My brother and I pedaled rusted bicycles across its cracked-tar surface, rolling flattened tires down the eroded clay bank that once served as a roughshod canoe launch and learning to swim beneath Winneboujou’s stretching shadow. We’d wade into the rapids above and let the current pull us deep into the bend below, plucking at shining objects on the sloping sand below, bits of lost tackle, wondrous flies, and old and rusted coins that may have fallen from lost canoes, or may have been throw like good-luck omens off the bridge and into a banked and swirling wishing well from the ghosts of days gone by.

The very name of Winneboujou still stops us in our tracks. We’ve seen the flicker that lies beneath. We were a blink in time rolling down the Brule River Valley, but Winneboujou looked down and watched us just the same. If it is it mortally possible for a bridge to mold human lives into its own, natural reflection of stone and iron in the water – the raw power of Winneboujou’s anvil was up to the task.

Today, the canoe landing has a fine parking lot and has moved residence upstream of the bridge. Highway B curves through Lake Nebagamon and shoots over Winneboujou in new-paved splendor. Rocks and gravel fill fortify bridge slopes where once upon a time bicycles and fishermen slid down a clay bank.

And yet, seekers of trout still pilgrimage in humbled awe to Winneboujou; Bamboo poles replaced by graphite rods, but held high nonetheless like banners of conquest in the riffles and pools. Canoes have turned from wood to fiberglass to plastic composite, but they still glide in smooth splendor above the bridge, and they are still just as prone to spill unwary occupants into the lower bend. The river is still banked in soaring pines, and the bridge still keeps watch over the Brule River’s endless journey into Lake Superior. Time blinks. Time moves on. Winneboujou breathes and wavers in shadowed light as it always has.

One might say it’s only nostalgia to write of a bridge as if it were actually alive. Rational minds will preach that magic is only a flight of fancy. Beneath red-pine shadows, in the furthest reaches of northwest Wisconsin, lies a bridge named Winneboujou. Go see for yourself. Tell me how to explain it in any other way.

John Luthens is a freelance writer from Grafton, Wisconsin. This story is an excerpt from his upcoming book, Writing Wild: Tales and Trails of a Wisconsin Outdoor Journalist. His first novel, Taconite Creek, is available on Amazon or at www.cablepublishing.com or by contacting the author at Luthens@hotmail.com