Fencerows: Deer Camp Stories

We sat beneath the branches of an oak deadfall that had crashed along the field edge in a lightning storm. The sun sank into the tree line. Hundreds of geese trumpeted and soared down in tightening circles, dropping into the picked corn with their honking echoing through our blind.

My son and I watched the spectacle in the last hour of the Wisconsin gun deer season. The geese put on such a show that we forgot about watching the field edge for deer. They were still living it up in the field stubble when we packed it in for the year and walked out in the shadows.

I reflected that I didn’t get to hunt as much as I wanted, but then again, does anyone? Those last moments of the season will stick in the memory vaults for a long time. It’s a good deer camp story.

Now, the season ended, it was time for more stories. I hadn’t seen most of my friends for nine days. I work with many of them, and come to think of it, I wondered if any of us had been at work at all. I vaguely remembered a couple of early mornings driving to the job still wearing a blaze orange jacket, gnawing on a leftover turkey leg and envious as hell of other trucks heading the opposite direction into the field.

There had been rumors from the north woods, but phone calls were in order to get the scoop before those stories got stretched out of proportion. I’d call a spade a spade, but lie is such a harsh word.

Dennis at Camp Kewaskum, in the northern Kettle Moraine Hills, was first on the phone tree list.

“I’m just sitting down to dinner, we’re having steaks,” he said.

“Venison?” I questioned.

|

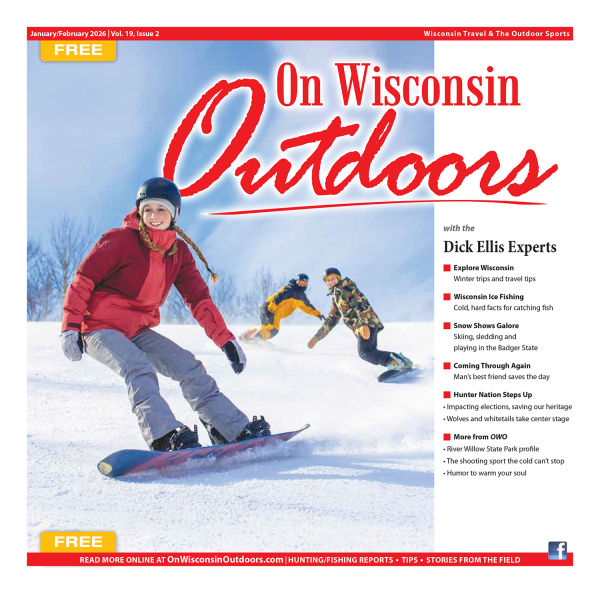

| The sun sets on the story of another deer season. |

“We got a few nice deer,” he hinted. “Say, you wouldn’t mind working for me next week during the muzzle loading season, would you?”

“I have to go, Dennis. The connection is breaking up and we’re just sitting down to dinner, too. We’re having leftover turkey.”

In the end, I agreed to work and Dennis gets to chase deer another week across the Kettle Moraine with the muzzleloader. I got a fine story in return.

They were in the truck coming back from hunting when the buck hauled across the field. They stopped to watch as the buck jumped the road and headed for an 8-foot high woven fence on the other side. They assumed the buck was going to jump the fence.

“Those fence posts were as big around as my leg,” said Dennis. “The buck plowed right into the post and snapped it off, bent the fencing back about 10 feet and broke off half of a six-point rack. Then it turned around and headed the other direction.”

His hunting party picked the broken antler out of the ditch. According to Dennis, the antler and the story made more rounds in camp than one of his bottles of homemade wine. It’s too bad they picked up the half-shed for evidence. The rack might have gone 30 points easy by the end of the season.

My friend Tom from up in Oconto County was next on the telemarketing list. He’d gone up into Michigan to hunt the weekend before the Wisconsin opener, returning eventually to his home confines in the Nicolet National Forest. Why he needed to trek to Michigan when he could literally step out his back door and into 650,000 acres of public hunting is beyond me. I guess buck fever doesn’t recognize state boundaries.

Between the Michigan and Wisconsin deer seasons, I couldn’t remember the last time I’d talked to him. I did try to text him one early morning, to tell him it was hunting ‘o clock and he better have his boots on. His wife texted back for him and said he was still sleeping and, in fact, had just fallen into bed at 3 a.m. I looked like that as far as Tom was concerned, not only was buck fever poor at geography, it couldn’t tell time either.

“Say, what kind of hunting does your wife let you get away with?” I asked Tom when he finally picked up the phone at the end of the season. Then the real story unfolded.

A friend called to ask Tom’s help in tracking a wounded deer. The spike buck had been hit at last light, and a pack of coyotes howled from the forest. If the deer went down in the dark, it likely wouldn’t be there in the morning.

“There was enough snow to mark a trail and we both had compasses,” related Tom. “The coyotes sounded like they were far away, and the next time they started barking, you swore they were right through the next stand of pines.”

Tom figured that they were about a mile and a half into the forest at the furthest point in their search.

“I kept checking my compass and my friend kept checking his,” Tom said. “It gets a little nerve wracking crashing through brush in the middle of the night. The blood trail thinned to nothing, but the coyotes kept on howling. By the time we finally called off the search and made it back to the truck, it was 2 a.m.”

They went back the next day but never found the deer. Tom figured it may have been hit in the leg. “Hopefully the deer made it,” he said.

“Hopefully your wife believed it,” I said.

On a brighter note, Tom told me he scoped out a new section along the Oconto River bottoms that looks to be prime trout fishing for next spring. I told him that even though he might be nocturnal, we’d probably wait for first light to go after the trout.

Nine days of deer stories, they are really what the season is about, and they’ll stretch further than any of today’s wireless phone contracts can cover; Even the insanely long ones.

As for my own story, it’s short and sweet. I didn’t get to hunt as much as I wanted, in fact, I never fired a shot, but I heard a lot of great stories and I’m eating venison sausage right now. My father-in-law got two, and he can’t eat ‘em both.